Piper dealers were horrified that their supplier wanted to them to sell a 'hugely' expensive twin. However, when launched, the

Apache leapt into the record sales charts. Now only a handful are still in existence locally and only one remains flying... and

earning its keep in the Eastern Cape.

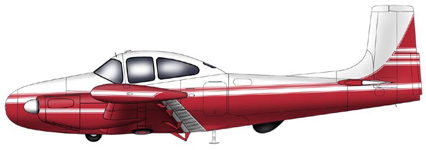

What you see here is South Africa's - perhaps even Africa's - last flying example of the world's greatest icon to 'affordable'

executive travel. Now all but disappeared into rude obscurity, the Piper Apache was the first ever, affordable multi-engined

business aeroplane. It became one of the company's most treasured and profitable products that led a reluctant Piper into the heady

realms of modern construction methods and for the first time, towards an altogether more sophisticated and discerning customer base.

Highly familiar and comfortable with its traditional tube and fabric singles, old man 'WT' Piper was not at first enthusiastic. The

Apache required the design of pump-fed twin engines, avionics and systems totally unfamiliar to its regular customers - it opened up

an entire new world to the homespun aeroplane builder.

The Apache was also Piper's first 'Indian'. Beaten into the air in November 1949 by Beechcraft's much larger Model-50 Twin Bonanza,

the first Apache flew in mid-1952 after a great deal of inter-departmental conflict over Piper's leap into high-technology

'big-aircraft' manufacture. It was one of Piper's key decisions to go ahead with the project although the push did not initially

come from the Piper family.

During the late forties and early fifties, Piper was emerging from the company's most painful era. It had managed to stay in

business following the appointment of corporate hatchet man, William Shriver, who had been appointed at the behest of the banks to

rescue Piper from the sudden crash of the aviation business in 1947. Much reviled by not only employees, but by the Piper family

itself, Shriver insisted 'WT' Piper, the old man, must move his office into one of the hangars. Bill Jr Piper, assistant treasurer,

was sent out on the road to sell aeroplanes and in order to keep creditors at bay and to reduce raw materials, the PA-15 Vagabond

was conceived. The Vagabond was considered an awful aircraft. Shriver refused permission for even a stripe to be painted along the

fuselage so that the price was kept as low as possible. The aircraft had no shock absorbers initially and was sold for the measly

fly-away sum of US$1,990.

At the end of 1948 Shriver had acquired the Stinson division of Consolidated Vultee as well as some 200 finished Voyagers. No money

changed hands but Piper simply increased its common stock and and handed a chunk over in payment. It was an acquisition detested by

the Piper family, especially as it was engineered by another banker: Joe Swan, a Shriver appointee.

Shriver ignored the family's complaints and shortly afterwards quit - Piper was beginning to recover and running a healthy company

had no interest for him. He packed his bags having saved the company although control was still with the banks. Shriver was replaced

by August Esenwein an engineer, who was to return Piper to prosperity again. Esenwein was notable for dispatching reams of memoranda

and being a stickler for procedure, and was soon to fall foul of the Piper family. Nevertheless, the company began to introduce

newer designs and launched an improved Vagabond, four-seat Pacer and the Super Cub. In early 1949, Esenwein made the decision to get

into the multi-engine business - something the Piper family had ruminated on on numerous occasions. It was to create a lot of

cynical argument within Piper - the family's view that it was an 'outsider' now wanting to push an entirely new design into

production only two years after the company was brought to its knees.

Esenwein had, like Shriver, little patience and was keen to buy in a design. He considered Ted Smith's clever and fast twin, later

to become the Aero Commander. He also looked at a homebuilt-type project called the Bauman Brigadier with pusher propellers. The

Brigadier was flown from California to Piper's Lock Haven plant in an epic flight that suffered numerous engine failures.

Nevertheless, Esenwein liked the Brigadier but the Piper family quickly convinced him that it would require too many costly

modifications to reach the market. WT Piper then persuaded Esenwein that his son, WT Jr, should be brought back from the west coast

and the company should employ a new sales manager. He called Ryan's Jake Miller who was tiring of Claude Ryan's obsession with

designing military aircraft and his lack of interest in the Navion. Miller had been trying, without success, to get Claude Ryan to

produce a twin-engined version of the Navion and jumped at the opportunity to launch the now favoured Ted Smith design.

The divergent views on which twin to build led to a January 1950 showdown in New York. WT Piper regained control of his company and

the Brigadier airframe was cast out to end its days at an engineering trades school in Williamsport. The high wing Smith design was

also discarded as being too costly and as legend has it, a redundant Stinson frame was dusted off (supported by the Stinson-like

shape of the side windows) and modified into a twin-engine, twin finned, low wing twin with a pair of anemic 125 hp Lycoming O-290

engines swiped from the Pacer production line. WT Piper continually interfered with the new design in his efforts to keep the costs

in line with traditional Piper customer expectations. Moreover, the company had gotten wind of Cessna's plans to build the sleek 310

from the many tradesmen and sales agents that shuttled between manufacturers during the fifties. It was difficult to keep secrets!

The Apache developed directly from a design by Stinson.

The twin-tailed Apache prototype is seen here.

(Hans Greonhoff via 1000aircraftphotos.com)

Apache development devoured around a million dollars of Piper's very precious resources. WT was going for broke - encouraged in no

small part by the sudden success of the company's new Tri-Pacer and some subcontracting work in aid of the US's Korean War efforts.

Even so, WT insisted the twin have fixed undercarriage to reduce cost and that it be a tube and fabric design. By March 1952, a

dreadful-looking mockup was assembled that at first seemed to satisfy all the conflicting ideas that came from each section of the

company's management. Just over a year later, the new twin was ready for flight testing and the first flight was given to Jay Myers,

whose grandfather had owned the farm on which the factory had been built - it was a typical Piper decision. Nevertheless Myers

landed after a 30-minute test flight in front of the entire Piper workforce. He wasn't happy.

"It's got the shakes" Myers reported after climbing out. Piper, with no previous experience in building this type of aircraft

brought in Grumman test pilot, Hank Kurt. Kurt reported exactly the same problem.

Mystified, Piper removed the twin fins and fitted a defunct Sky Sedan single vertical stabilizer and rear fuselage. This improved

matters somewhat but the vibration remained. A model was constructed and sent to the Pennsylvania State University, who had a wind

tunnel and Piper upset the staff by feeding smoke from a paraffin-dipped cigar into the apparatus. The tests showed nothing and

Piper resorted to attaching short tufts of yarn to the airframe in an effort to find where the vibration was coming from. At last,

this rudimentary method brought immediate success and the engineers discovered an airflow vortex at the rear of one of the engine

cowlings that struck the vertical tail causing the vibration. It was cured by filleting a triangular shape to the outboard cowling

and fuselage side where the wing joined the main structure. It also dawned on Piper that their new aircraft looked so old fashioned,

it would never sell - a new twin had to at least look sleek. The fabric fuselage had to go but redesigning the cabin invited a level

of structural design Piper didn't at the time possess. Consequently, the tubular cabin structure was retained but the rear fuselage

and wings were re-made from alloy. Moreover, 150 hp engines were installed as well as constant speed, fully feathering propellers.

Howard Piper came up with the idea of calling it the 'Apache' and Jake Miller suggested it should be the start of a whole series of

aircraft named after Indian tribes.

Apaches made affordable corporate and charter transports, as well

as twin-engine trainers. (Ron Dupas, 1000aircraftphotos.com)

There was a great deal of fear over the new twin's retail price, which had escalated to the unheard of (for a Piper) level of

US$32,500. Beechcraft's Twin Bonanza was selling for US$70,000 and Cessna's new 310 would be sold for almost US$50 000. Piper's

distributors, used to retailing Cubs and Tri-Pacers, were horrified at the price of the Apache when first deliveries were made in

February 1954. However, before the end of the year, Piper had completed 101 Apaches with orders for 200 more.

The Apache was completely outclassed by its better-performing and roomier competitors. However, at the price, it was in a market of

its own and Piper had succeeded in launching a volume-production light twin, much cheaper to operate than anything else then in

production. Moreover, the Apache was soon acclaimed for its gentle handling characteristics, low wing loading and ability to get in

and out of short airstrips. The Apache also motivated WT Piper, well into his seventies, to get a twin conversion and after a few

hours instruction, soloed the Apache on July 21, 1954 - it was his first and last solo flight in a twin - he gave up flying

altogether three years later.

Eventually the Apache gave way to the more powereful Aztec.

(Piper)

The Apache was sold in B, C and D models between 1955 and 1957. Along with various minor improvements came increases in gross weight

and fuel capacity as well as optional radio equipment. The aircraft was further offered in three 'comfort' levels and from 1955 a

fifth seat was provided. In 1958, Piper introduced 160hp Lycomings in its E-model and yet another weight increase. In 1960, an

additional side window was provided. The production line was finally closed in 1962 after Piper completed 2,047 aircraft. The reins

had been taken up by the larger PA-23-250 Aztec, which had been introduced in 1959. However, Piper still produced an Apache model -

a lower priced Aztec with five seats only and powered by a pair of 235hp Lycomings known as the Piper PA-23-235 Apache but only 118

were made and production was halted in June 1966.

Late model Apaches were characterised by extra windows and the

Aztec's swept tail. (Ron Dupas, 1000aircraftphotos.com)

> Home

> Contributors

> Brochures

> Publications

> Stories

> Models & Toys

> Collector Cards

> Flight Simulators

> For Sale

> Links